Introduction

This paper aims to show that empathy is central to successful language learning and to making language teaching a more compassionate and fairer profession. I begin by exploring what empathy is, its three main components: cognitive empathy; affective empathy and empathetic concern, and its neurological foundations. I draw on general education literature to present what research findings suggest about the role of empathy in education and the characteristics of empathic teachers. I then draw on language education literature and research to support my argument that empathy is particularly important in language education. I examine whether there is an empathy deficit in language teaching and look at hindering factors that may make it challenging to embed a culture of empathy in the profession. Finally, moving from theory to practice, I explore how we could explicitly develop empathy as a skill among teacher trainers, teachers and learners.

What is empathy?

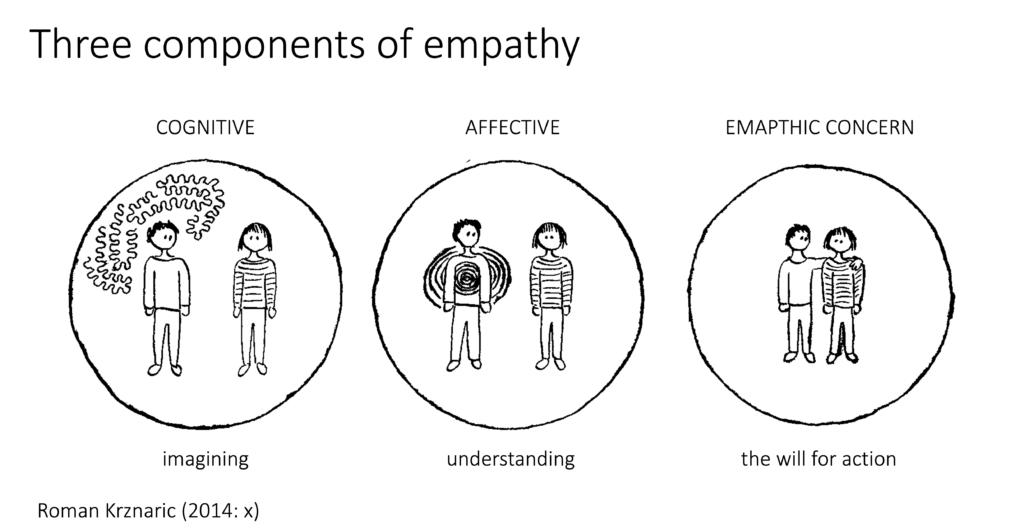

Empathy is a complex construct and has several components. Roman Krznaric’s definition (2014) is particularly nuanced and recognises the multiple components of empathy.

‘Empathy is the art of stepping imaginatively into the shoes of another person, understanding their feelings and perspectives, and using that understanding to guide your actions’ (Krznaric, 2014, p. x).

Krznaric’s definition recognises three components of empathy. The first is a cognitive part: ‘stepping imaginatively into the shoes of another person’ (Krznaric, 2014, p. x). The cognitive part is the drive to identify what another person might be thinking or feeling, and putting yourself in someone else’s shoes and imagining what is going on in their minds.

The second component is affective: ‘understanding their feelings and perspectives’ (Krznaric, 2014, p. x). It is the emotional reaction to someone else’s thoughts and feelings. The affective component is about shared emotional response.

Both the cognitive component and the affective component must be combined to create the third component, empathic concern: ‘using that understanding to guide your actions’ (Krznaric, 2014, p. x). Empathic concern is an emotional response of compassion and concern that leads us to care about the other person’s welfare, and to want to take action to help them if they are in need. Empathic concern involves the will to do something for the other person. Cognitive and affective empathy alone are not enough for pro-social behaviours.

Figure 1: Three components of empathy

Parent-child attachment is key in the formation of empathy. Children must have experienced empathic treatment themselves if they are, in turn, to develop empathy (Hogan, 1973). Carl Rogers argued that empathy at an early stage in a relationship, predicts later success in that relationship (1975). He believed that empathy can potentially be developed by training. There is an overwhelming consensus amongst experts that we can develop our empathic potential throughout our lives (Cooper, 2011; Galinsky, & Moskowitz, 2000; Gordon, 2009; Hargreaves, 1972; Howe, 2013; Krznaric, 2014; Rogers, 1975).

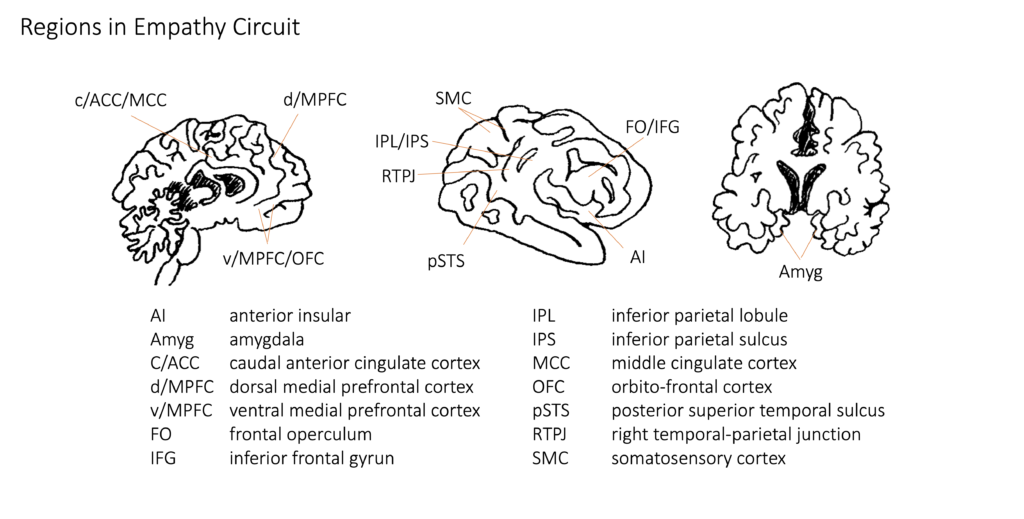

What are the neurological foundations of empathy?

Having defined empathy and looked at its various components, we now need to explore the neurological foundations of empathy. To do this we need to consider a moment of scientific serendipity. In 1990, at the University of Parma, a team of neuroscientists led by Giacomo Rizzolatti accidentally discovered ‘mirror neurons’ while conducting experiments on monkeys (di Pellegrino et al. 1992). Rizzolatti and his team recorded that a particular region of the pre-motor cortex was activated when a monkey picked up a peanut. Then, completely by accident, they noticed that the same region lit up when the monkey happened to see a researcher pick up a nut even though the monkey had not moved an inch. The brain had responded as if the monkey had grasped the nut itself. Subsequent brain imaging experiments have shown that the inferior frontal cortex and superior parietal lobe are active when the person performs an action and also when the person sees another individual performing an action. It has been suggested that these brain regions contain mirror neurons.

However, it is important to understand that there is no simple empathy centre in the brain.

Mirror neurons are just one part of a much more complex ‘empathy circuit’ comprising 14 different but interconnected brain regions. When we empathise with another person this network of regions is activated.

Figure 2: Regions in empathy circuit

These neurological insights remind us what an extraordinary and complex capacity empathy is.

Why is empathy important in society?

Humans are fundamentally social beings and it is in our genetic nature to be neuro-biologically connected to others (Cacioppo et al. 2010; Dunbarr, 1998; Libermann, 2013). Rifkin, argues that empathy ‘becomes the thread that weaves an increasingly differentiated and individualised population into an integrated social tapestry, allowing the social organism to function as a whole’ (2010: 26). Empathy is also vital for a healthy democracy as it ensures we listen to different perspectives and that we hear and feel other people’s emotions. Without empathy democracy would not be possible (Howe, 2013).

Given the importance of empathy in society, its rapid decline, at least in the West, which Barrack Obama has called ‘the empathy deficit’, is alarming (Northwestern University, 2008). A study by Konrath, O’Brien and Hsing (Konrath et al., 2011) at the University of Michigan in 2010 revealed a dramatic decline in empathy levels amongst college students between 1980 and 2010. College students in the USA today demonstrate about 40 percent less empathy than their counterparts of 20 or 30 years ago. Konrath, O’Brien and Hsing think a number of factors may be responsible for this empathy deficit: more people living alone and spending less time engaged in social and community activities which nurture empathy; the increased use of digital technology and the rise of social media; and a hypercompetitive social environment and inflated expectations of success.

Why is empathy important in education?

In education there is a wide recognition of the importance of emotions and the development of empathy as part of moral development (Best, 2000; Cooper, 2011; Cross, 1995; Gordon, 2009; Lang et al., 1998; Rogers, 1975). Daniel Goleman, author of the best-selling book Emotional Intelligence, argues that ‘Schools have a central role in cultivating character by inculcating self-discipline and empathy, which in turn enable true commitment to civic and moral values’ (1995, p. 286).

An extensive body of research suggests that in all educational settings high-quality relationships between the teacher and students, and among students are important for students’ school engagement, motivation and learning (Berndt & Keefe, 1996; Birch & Ladd, 1996; Furrer et al., 2014; Juvonen et al., 2012; Klem & Connell, 2004; Martin & Dowson, 2009). Empathy is essential in creating these quality relationships and would appear to be central to all successful learning and development. Child advocate, Mary Gordon, reflects the importance of empathy and the high-quality relationships we form with our students when she argues that ‘to teach children, we must first reach them’ (2009: 194).

What are the characteristics of empathic teachers?

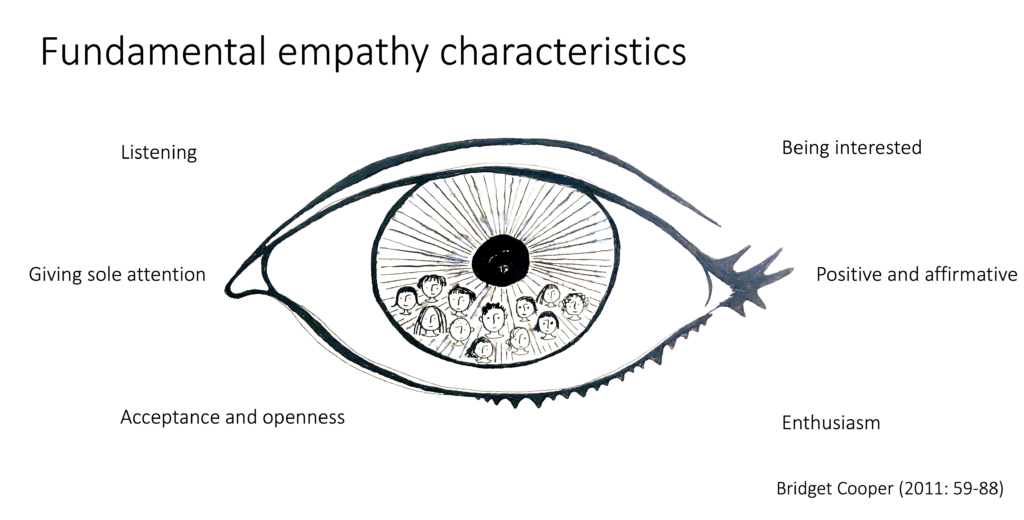

Characteristics of teacher empathy fall into three broad areas: functional; fundamental and profound (Cooper, 2011).

Figure 3: Functional empathy characteristics

Functional empathy is demonstrated when teachers create a mental model of a group of students. To use functional empathy, teachers need to have a rich social, emotional and academic understanding of a whole group of students and to establish fair and reasonable group rules and good manners between the teacher and students. While using functional empathy, teachers often categorise students into different types and groups in order to assess them and cater for their needs. Functional empathy is absolutely essential in the classroom as it provides cohesion and security, creates understanding and a positive group climate. However, a teacher who only uses functional empathy does not cater to the needs of individual students who do not conform to the group stereotype. Most teachers try to supplement this functional empathy with fundamental empathy and profound empathy for individual students.

Figure 4: Fundamental empathy characteristics

Fundamental empathy is needed to initiate empathic relationships and can be observed in the type of social interaction that most people use to engage in relationships with others in daily life. There are a number of characteristics of teachers who use fundamental empathy. These teachers are accepting and open to students. By being open themselves and sharing their own experiences, teachers eventually learn more about the student. They give focused sole attention to students and this helps to maximise engagement, communication and learning. They listen and value individual students by hearing their perspective. They show interest in students and this makes the student feel valued and worthy. They directly praise students. Direct praise is particularly important for students from minority groups, and students with Specific Learning Difficulties who may receive little praise elsewhere in the educational system. Finally, these teachers are enthusiastic about both their subject and their relationship with their students.

Fundamental empathy initiates the focused interactive relationships that support engagement, interaction and learning. The active listening and interest of the empathic teacher begins this engagement with the student, which over time can develop into emotional attachment. The enthusiasm of these teachers begins to engage students in learning at an emotional level.

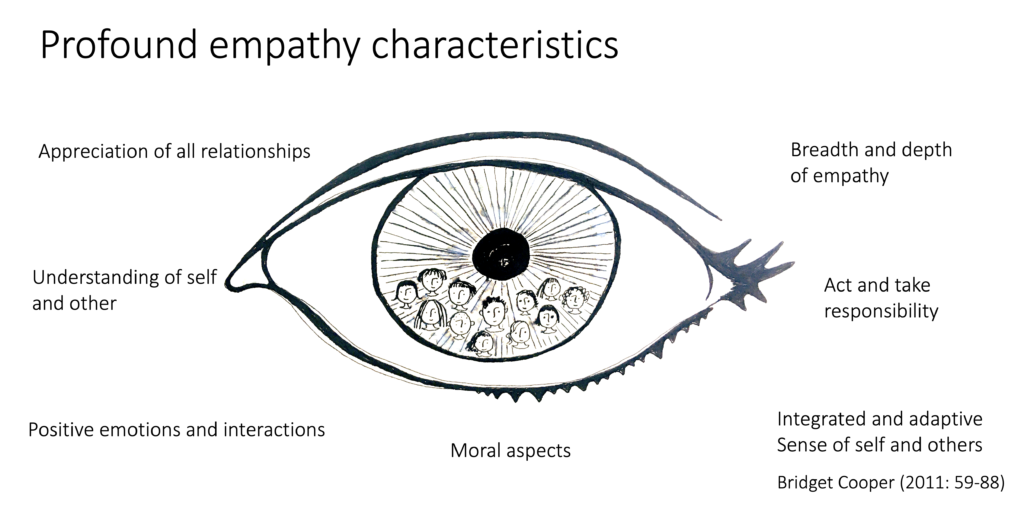

Figure 5: Profound empathy characteristics

Profound empathy is of a higher order than functional or fundamental empathy as its characteristics show deeper and broader levels of understanding. There are a number of characteristics of teachers who use profound empathy. Profoundly empathic teachers act to create positive emotions. They realise that positive personal interaction needs sole attention and individual quality time. They make time for interactions with students before and after class, in breaks, at lunchtime and after school. These teachers are aware of the importance of knowing themselves and of trying to get inside their students’ thinking and feelings. They remember their own reactions and their own children’s reactions to teachers. They lay great stress on the importance of relationships in teaching and learning and empathise deeply with a wide range of students. They build up an encyclopaedic knowledge of all students. They take responsibility for the well-being of students, as well as their academic development. They are highly adaptive and aware of the different roles they adopt with different students. They build extremely rich mental models of their students and develop deep attachments. Finally, profoundly empathic teachers try to be good people, to do the right thing and to support others. The moral behaviour of the teacher is naturally mirrored by students.

When we examine the literature, profound teacher empathy reminds us of Carl Rogers’s synonym for empathy, ‘sensitive understanding’ (1975) and his concept of ‘unconditional positive regard’ for the other (1956); Earl Stevick’s concept of ‘presence of harmony’ (1980); Nel Noddings’s concept of ‘engrossment’ (1986) and Iris Murdoch’s concept of ‘loving attention’ (1970) that promotes moral development.

Why is empathy particularly important in language education?

As we have already seen, empathy and high-quality relationships are central to all successful learning and development. However, in contemporary language classrooms where communicative competence is a central goal and which use communicative language teaching and learner-centred approaches which are highly social and interpersonal in nature, high-quality relationships are particularly important. In 2016 Christina Gkonou and Sarah Mercer carried out the first large-scale study on the emotional and social intelligence of English language teachers across the globe. The results of the quantitative survey revealed that English language teachers generally scored highly on the emotional and social intelligence scales (2017). Gkonou and Mercer’s qualitative research findings show that the majority of teachers emphasised the importance of having meaningful high-quality relationships with their students, and pointed to four main characteristics of these quality relationships: empathy; respect; trust and responsiveness. Empathy was the most mentioned characteristic of meaningful high-quality relationships with students. The key to achieving these meaningful high-quality relationships with our students and other teachers would seem to be our capacity to empathise.

Given the increasingly multicultural and multilingual nature of the language classroom in many parts of the world, language teachers and learners need to develop intercultural skills,

and empathy has a vital role to play in promoting intercultural competence which is a key facet of communicative competence (Rasoal, et al., 2011; Wang, et al., 2003). As Gkonou and Mercer argue, nurturing empathy, ‘can mediate intercultural understanding, increase self-awareness and an awareness and appreciation of other cultures, and make learners open to others’ (2017, p. 8). Empathy is even more important in the ESL classroom where students often feel inadequate as they have gone from feeling confident in classrooms in their own countries to classrooms in a foreign country where communication may be very difficult (Cooper, 2011). To boost the self-confidence of ESL students, the teacher needs a huge amount of sensitivity and empathy.

In sum, empathy is particularly important in language education because of its focus on communication, social interactions and cultural diversity (Mercer, 2016).

Is there an empathy deficit in language education?

When we examined the importance of empathy in society, I referred to what Barrack Obama has termed the empathy deficit. We are now going to explore if an empathy deficit exists in language education. Language teachers are aware of the importance of empathy in successful learning, and want to be and try to be empathic. Undoubtedly one of the most effective ways of embedding a culture of empathy in language teaching is for teachers to act as role models of an empathic and moral person. However, there are a number of factors which may hinder teachers’ ability to be empathic and for us to embed a culture of empathy. You will probably already be aware of these factors, but perhaps it is the first time you have read about them related to the construct of empathy.

One hindering factor is an over-emphasis on curriculum, assessment, certification and competition. Schools, head teachers and teachers who overstress the importance of exam results, certification and competition may send negative messages to students with Specific Learning Difficulties and their families, and make it more difficult for empathic teachers to support these students. Curriculum, assessment and league tables may also reduce time for empathy, and social and emotional education.

Another hindering is the exclusion of certain groups of people from coursebooks. Global ELT coursebooks try to avoid certain issues that may cause offence, often summarised under the PARSNIPs acronym: politics, alcohol, religion, sex, narcotics, isms (such as socialism or atheism), and pork. The reason publishers censor material is that they want to sell books in as many markets as possible and do not want to upset local sensibilities. However, I would argue that the PARSNIPs approach is fundamentally flawed as it is based on a one-size-fits-all method of content creation. It is certainly economic, but it is not necessarily ethical because it excludes and ‘others’ many people as it denies their experiences, life choices and belief systems and it may make it more difficult for students to empathise with these groups of people (Garmroudi, A. 2018; Gray, J. 2002).

I believe that all of us – teachers, teacher trainers, managers, writers and publishers – need to be braver and push for more inclusivity in ELT materials. A recent initiative to make ELT coursebooks more inclusive is Raise Up by Ilá Coimbra and James Taylor (2019) which is a coursebook which represents groups of people such as working-class people, homosexuals, indigenous people, refugees, the elderly and disabled people who have traditionally been excluded from coursebooks.

Another hindering factor is native-speakerism which Silvana Richardson spoke about eloquently and passionately in her seminal IATEFL plenary in Birmingham in 2016. During my career many of the very best teachers I have met have been ‘non-native English-speaking teachers’ (‘NNESTs’). However, there is still widespread discrimination in both the recruitment and conditions for this group of teachers. The most common justification for this discrimination is that students prefer ‘native English-speaking teachers’ (‘NESTs’). However, when we examine the literature there is no conclusive evidence that students actually prefer ‘NESTs’ over ‘NNESTs’ (Cheung, 2002; Cook, 1999; Kelch and Santana-Williamson, 2002; Walkinshaw and Duong, 2012).

I feel there has to be equity for both ‘NESTs’ and ‘NNESTs’. TEFL Equity Advocates is an organisation set up by Marek Kiczkowiak which fights to achieve this equity (see https://teflequityadvocates.com/). Those of us in the profession who are ‘native speakers’ of English should imagine what it feels like to be a person who has learned English to a high level, studied pedagogy at university, pursued professional development, and then to be rejected for a job or receive a worse salary and conditions because their native language is not English. As Richardson (2017, p. 87) concludes, ‘The challenge and opportunity we are faced with is the re-construction of a profession where all competent, professional EFL teachers are treated equally and the diversity we all bring is valued.’

A general hindering factor is the undervaluing of teachers. Teachers feel undervalued and teacher morale is a major problem. One of the reasons teachers feel undervalued are the long hours, low pay and precarity that many teachers endure. We know that if workers are overworked, stressed and tired, this has a negative impact on their capacity to empathise. The solution certainly involves teachers becoming members of local unions or forming a union if one does not already exist, in order to try to protect and improve their rights, pay and conditions, and fight for fair compensation when schools close. Another option is to join the Teachers as Workers Special Interest Group set up by Paul Walsh which aims to address the working conditions of English language teachers (see https://www.teachersasworkers.org/). But, perhaps, it also involves teachers organising themselves collectively (Kerr & Wickham, 2016). A successful example of collective organisation is Cooperativa Serveis Lingüístics de Barcelona, a cooperative set up by teachers in Barcelona who offer language classes, teacher training courses, translations and services for language professionals (see https://www.slb.coop/).

Another hindering factor is the poor mental health of many language teachers. People who have poor mental health may find it more difficult to empathise with other people (Greenspan & Benderley, 1998). Teaching has one of the highest rates of stress and burnout, which interfere with mental health (Grayson & Alvarez, 2008; Jennings et al., 2017; Miller et al., 2019). In a 2020 UK study by the charity Education Support: 31% of teachers said they had experienced a mental health problem in the past academic year; 84% of teachers described themselves as ‘stressed’ or ‘very stressed’; and 74% of teachers have considered leaving the profession due to pressures on their health and wellbeing (Education Support 2020).

Language teachers may be even more susceptible to poor mental health because of the poor working conditions we explored earlier. In 2017 Phil Longwell carried out research into the causes of, and possible solutions to, poor mental health in English language teaching. In the qualitative part of his study, teachers wrote about their experience of poor mental health in the staffroom and classroom. Here are two examples:

‘I think poor and unstable working conditions, instability caused by moving from one country to another quite regularly, pressure to ‘perform’ in the classroom and always seem to be happy and in a good mood even when you are not, are all factors.’

‘Unfair/difficult working conditions, professional instability, irrational expectations from employers, general social underestimating of my profession, working load that is not reflected in work pay. The latter is a main cause of frustration and feelings of depression.’

(Longwell, 2017)

Both teachers refer to poor working conditions and precarity as causes of poor mental health. I believe ministries and schools can do a lot to improve their teachers’ mental wellbeing by improving working conditions.

How can we foster empathy?

The final part of this paper explores ways that empathy can be explicitly developed in our classrooms. One way for teachers and trainers to become more empathic is to keep a reflective journal to reflect on the perspectives of colleagues and students, and to record every time we notice an instance of ourselves, a student or a colleague being empathic. Reflecting on a diversity of perspectives is important, as we need to be able to have empathy for all our students and colleagues, not just those with whom we find it easy to empathise (Cooper, 2011).

As empathy is promoted whenever we focus on the human experience, read a novel, act in a play, look at a painting, or watch a film, perspective-taking activities and the arts can also be used to foster empathy among students (Howe, 2013).

The use of role-play is an especially effective method for fostering empathy. As role-play is a familiar type of activity in communicative language teaching classrooms, it is easy to adapt tasks to focus on empathy. However, to maximise the potential for students to foster empathy, they must be given time to prepare their role and get into character. Empathy-fostering questions such as ‘What kinds of things do you think they like and dislike?’ and ‘What and who do they care or worry about?’ support students in getting into character.

Fiction also helps to extend empathy, as it often focuses on the psychology of characters and their relationships. We should encourage students to read fiction about people different from them and people from marginalised groups. After reading a novel, short story or reader we can ask students to reflect using empathy-fostering questions which focus on the psychology of the characters, such as ‘How would you feel if you were that person?’ and ‘What would you have done differently in that situation?’

We can also show films about people who are very different from our students and about marginalised people. For example, the short film Ali’s Story (Freedom from Torture, 2012) tells the story of a young Afghan boy who has to flee his country because of war and becomes a refugee in Britain. Asking students to discuss empathy-fostering viewing questions after watching such films (e.g. ‘How do you think Ali might be feeling? How do you know?’ and ‘What led Ali to make that choice?’) helps students to consider the perspectives of people different from themselves.

Another way of taking someone else’s perspective is through the use of paintings and photographs. We can show students a painting or photo that includes a person and give them a perspective taking instruction such as:

‘Imagine a day in the life of this individual as if you were that person, looking at the world through her eyes and walking through the world in her shoes.’ (Galinsky & Moskowitz, 2000)

A number of Visible Thinking Routines (Ritchhart, et al, 2011) are also valuable tools for fostering empathy. The Step Inside routine asks students to step inside the role of a character from a picture they are looking at, a short film they have watched or a story they have read, and to imagine themselves inside that point of view. Students then speak or write from that chosen point of view. Three core questions guide students in this routine:

1. What can the person perceive?

2. What might the person know about or believe?

3. What might the person care about?

Final reflections

I would argue that the EdTech experiment during the pandemic has been a stark reminder of the vital importance of schools not just as places of learning but also of socialisation, community and caring. As we move from pandemic education to post-pandemic education, teachers will have to care for students who may have suffered COVID, whose relatives may have had COVID or even died from the virus, who may have mental health issues, and whose learning may have been negatively affected by the pandemic. This is a huge challenge which requires an enormous amount of empathy. With the support of profoundly empathic teachers, post traumatic growth and wisdom among our students may be possible, but teachers need the right conditions to be able to help their students, and face-to-face classes where the constant human dialogue necessary for caring and learning best take place are an essential part of this. Teachers may also need training in social and emotional learning and trauma-informed practice. When the inevitable reimagining of post-pandemic education comes, we should reimagine how we can optimise language learning and as an integral part of that, we should also reimagine inclusivity, entrenched underfunding, and teachers’ pay and conditions.

Illustrations by Jade Blue.

This article was first published in IATEFL 2021 Conference Selections.

You can download a PDF of the article here.

If you’re interested in the role of empathy in language teaching, check out our Empathy in Language Teaching course.

Check out the course

References

Berndt, T. J., & Keefe, K. (1996). Friends’ influence on school adjustment: A motivational

analysis. In J. Juvonen & K. R. Wentzel (Eds.), Social motivation: Understanding children’s

school adjustment (pp. 248–278). Cambridge University Press.

Best, R. (2000). Empathy, experience and SMSC (Spiritual, Moral, Social and Cultural education). Pastoral Care, December.

Birch, S. H., & Ladd, G. W. (1996). Interpersonal relationships in the school environment

and children’s early school adjustment: The role of teachers and peers. In J. Juvonen

& K. R. Wentzel (Eds.), Social motivation: Understanding children’s school adjustment (pp.

199–225). Cambridge University Press.

Cacioppo, J.T., Berntson, G.C. & Decety, J. (2010). Social neuroscience and its relationship to social psychology. Social Cognition 28(6), 675–685.

Cheung, Y.L. (2002). The Attitude of University Students in Hong Kong towards Native and Non-native Teachers of English.(Unpublished master’s thesis). The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Coimbra, I., & Taylor, J. (2019). Raise Up. Taylor Made English.

Cook, V. J. (1999). Going beyond the native speaker in language teaching. TESOL Quarterly 33(2). 185–209.

Cooper, B. (2011). Empathy in education: Engagement, values and achievement. Bloomsbury.

Cross, J. (1995). Is there a place for personal counselling in secondary school? Pastoral Care in education, 13(4).

di Pellegrino. G., Fadiga, L., Fogassi, L., Gallese, V., & Rizzolatti, G. (1992). Understanding motor events: a neurophysiological study. Experimental Brain Research, 91 (1), 176-180.

Dunbarr, R.I.M. (1998). The social brain hypothesis. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News and Reviews 6(5), 170–190.

Education Support. (2020). Teacher wellbeing index 2020. https://www.educationsupport.org.uk/resources/research-reports/teacher-wellbeing-index-2020

Freedom from Torture. (2012, June 22). BBC Learning: Seeking Refuge’ Series – Ali’s Story [Video]. Vimeo. https://vimeo.com/44516196

Furrer, C.J., Skinner, E.A., & Pitzer, J.R. (2014). The influence of teacher and peer relationships on students’ classroom engagement and everyday motivational resilience. National Society for the Study of Education, 113(1), 101–123.

Galinsky, A. D., & Moskowitz, G. B. (2000). Perspective-taking: Decreasing stereotype expression, stereotype accessibility, and in-group favoritism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78, (4), 708-724.

Garmroudi, A. (2018, January 11). Parsnips, a protest BETTblogs. https://digitallearningassociates.com/whats-new/2018/1/24/bettblogs-parsnips-a-protest

Gkonou, C. & Mercer, S. (2017) Understanding emotional and social intelligence among English language teachers. British Council.

Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional intelligence: Why it can matter more than IQ. Bantam Books.

Gordon, M. (2009). Roots of empathy: Changing the world child by child. The Experiment.

Gray, J. (2002). The global coursebook in English language teaching. In D. Block, & D. Cameron (Eds.) Globalization and Language Teaching (pp. 151–167). Routledge.

Grayson, J. L., & Alvarez, H. K. (2008). School climate factors relating to teacher burnout: a mediator model. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24(5), 1360–1363.

Greenspan, S. I., & Benderly, B. L. (1998). The growth of the mind: And the endangered origins of intelligence. Perseus Books.

Hargreaves, D. H. (1972). Interpersonal relations and education. Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Howe, D. (2013). Empathy: What it is and why it matters. Palgrave Macmillan.

Jennings, P. A., Brown, J. L., Frank, J. L., Doyle, S., Oh, Y., Davis, R., Rasheed, D., DeWeese, A., DeMauro, A. A., Cham, H., & Greenberg, M. T. (2017). Impacts of the CARE for teachers program on teachers’ social and emotional competence and classroom interactions. Journal of Educational Psychology, 109, 1010–1028.

Juvonen, J., Espinoza, G., & Knifsend, C. (2012). The role of peer relationships in student

academic and extracurricular engagement. In S. Christenson, A. Reschly, & C. Wylie

(Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 387–401). Springer Science.

Kelch, K., & Santana-Williamson, E. (2002). ESL students’ attitudes toward native and non-native speaking instructors’ accents. The CATESOL Journal 14, 57–72.

Kerr, P. & Wickham, A. (2016). ELT conversation: ELT as an industry. In T. Pattison (Ed.), IATEFL 2015 Manchester Conference Selections (pp.75–78). IATEFL.

Klem, A. M., & Connell, J. P. (2004). Relationships matter: Linking teacher support to

student engagement and achievement. Journal of School Health, 74, 262–273.

Konrath, S.H., O’Brien, E. H., & Hsing, C. (2011). Changes in dispositional empathy in American college students over time: a meta-analysis. Personal Social Psychological Review, 5 August.

Krznaric, R. (2014). Empathy: A handbook for revolution. Rider.

Lang, P, Katz, Y. & Menezes, I. (Eds.) (1998). Affective education: A comparative view. Cassell.

Longwell, P. (2018, April 4). The mental health of English language teachers: Research findings Teacher Phili. https://teacherphili.com/2018/04/04/the-mental-health-of-english-language-teachers-research-findings/

Libermann, M. D. (2013). Social: Why our brains are wired to connect. Oxford University Press.

Martin, A. J., & Dowson, M. (2009). Interpersonal relationships, motivation, engagement,

and achievement: Yields for theory, current issues, and educational practice. Review of

Educational Research, 79, 327–365.

Mercer, S. (2016). Seeing the world through your eyes: Empathy in language learning and teaching. In P. D. MacIntyre, T. Gregersen, & S. Mercer, (Eds.), Positive Psychology in SLA (pp. 91–111). Multilingual Matters.

Miller, L., Musci, R., D’Agati, D., Alfes, C., Beaudry, M. B., Swartz, K., & Wilcox, H. (2019). Teacher mental health literacy is associated with student literacy in the adolescent depression awareness program. School Mental Health 11(2), 357–363.

Murdoch, I. (1970). The sovereignty of good. Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Noddings, N. (1986). Caring – A feminine approach to ethics and moral education. University of California Press.

Northwestern University. (2008, July 16). 2006 Northwestern Commencement – Sen. Barack Obama [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2MhMRYQ9Ez8&ab_channel=NorthwesternU

Stevick, E. (1980). Teaching Languages: A Way and Ways. Heinle.

Rasoal, C., Eklund, J., & Hansen, E. M. (2011). Toward conceptualization of ethnocultural empathy. Journal of Social, Evolutionary, and Cultural Psychology, 5(1), 1–13.

Richardson, S. (2017). The ‘native factor’: the haves and the have nots … and why we still need to talk about this in 2016. In T. Pattison (Ed.), IATEFL 2016 Birmingham Conference Selections (pp.77–89). IATEFL.

Rifkin, J. (2010). The empathic civilization: The race to global consciousness in a world in crisis. Polity.

Ritchhart, R., Church, M., & Morrison, K. (2011). Making thinking visible: How to promote engagement, understanding, and independence for all learners. Jossey-Bass.

Rogers, C. R. (1956). Client-centered therapy: Its current practice, implications and theory. Houghton Mifflin.

Rogers, C. R. (1975). Empathic: an unappreciated way of being. The Counselling Psychologist, 5(2), 2, 5–7.

Walkinshaw, I., & Duong, O. T. H. (2012). Native and non-native speaking English teachers in Vietnam: Weighing the benefits. TESL-EJ 16(3), 1–17.

Wang, Y.-W., Davidson, M. M., Yakushko, O. F., Savoy, H. B., Tan, J. A., & Bleier, J. K. (2003). The scale of ethnocultural empathy: Development, validation, and reliability. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 50(2), 221–234.